By Lauren Meisner, founder of Centennial World and host of Infinite Scroll

Bumble’s anti-celibacy campaign took a misguided stab at young women’s boundaries, sparking immediate backlash. Users queried if any women were involved in this rebrand, while marketers suggested that perhaps the brand didn’t pre-test this campaign. However, as an internet culture journalist, I see this fumble as a fundamental misunderstanding of why Gen Z women are setting these boundaries in the first place.

Despite the supposed era of ‘cancel culture,’ Gen Z have proven they are not ruthless and unforgiving. Bumble’s well-executed apology is a prime example of how brands can make amends with this generation and recover quickly from mistakes.

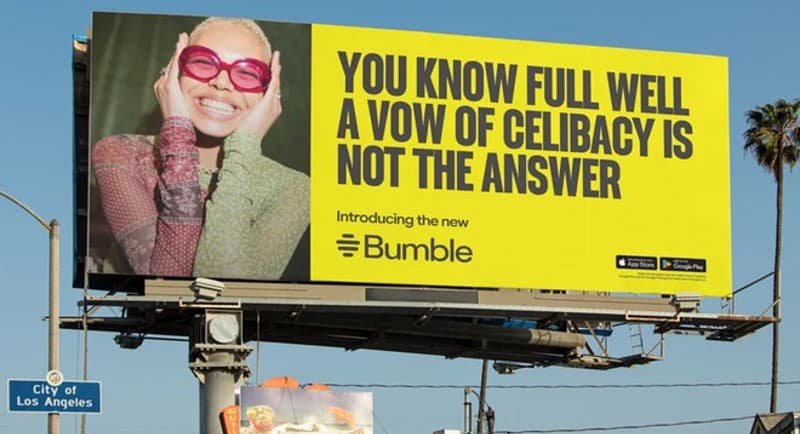

After updating its features and launching a rebrand targeted at young women who are “exhausted” by dating, feminist dating app Bumble rolled out a series of anti-celibacy billboards. The billboards, which quickly went viral for all the wrong reasons, featured text like, “You know full well a vow of celibacy is not the answer” and “Thou shalt not give up on dating and become a nun.” They appeared to be in response to the growing voluntary celibacy movement among millennial and Gen Z women— who make up 61% and 26% of dating app users, respectively.

Gen Z dating experiences are notably different from previous generations because of how the social media landscape has evolved.

Over the past few years, we have seen a renaissance of regressive ideas about feminism and gender roles online. Masculinity influencers like Andrew Tate have millions of followers and tradwife propaganda videos fill our feeds.

The nature of social media algorithms, particularly TikTok’s For You Page, have made it easier for Gen Z men to be exposed to misogynistic, anti-woman, and incel ideologies. Previously, this content lurked in niche corners of the internet like 4Chan or Reddit forums. The sheer volume and accessibility of misogynistic content online have made it more socially acceptable for young men to be outwardly anti-woman.

However, these algorithms are not exclusive to young men. Most young women will also be fed versions of this content. As a result, Gen Z women are more aware of how dangerous men can be. This shift in the online landscape has also contributed to some scary real-world consequences, like the ongoing war against women’s reproductive rights in America.

Ultimately, as TikTok users are involuntarily exposed to misogynistic content, many social media pundits have started questioning how algorithms manipulate our experiences in the online world. This, in turn, has left many Gen Z women feeling that the algorithms on dating apps are designed to retain users— instead of helping them find partners. This disillusionment is further intensified when online daters, particularly minorities, face misogyny and harassment within these spaces.

With this context, it’s no surprise that the anti-celibacy billboards did not go over well with Gen Z. But this is where Bumble’s fumble ends.

As the backlash intensified, the brand released a statement on 13 May addressing users’ concerns.

Bumble explained that the campaign was a mistake, said it’s removing the ads, and will be donating to the National Domestic Violence Hotline in the U.S., as well as other organisations that support women. The dating app also said the billboard spaces will be offered to those organisations to display “an ad of their choice” for the remaining duration of the ad run.

This apology was received well. Really well.

Bumble did several things right with their response that helped get Gen Z back on-side:

1. Acted quickly

2. Acknowledged the hurt they caused

3. Detailed why people were hurt by this campaign

4. Expressed remorse

5. Offered to make amends in a tangible way

Bumble’s willingness to accept responsibility and take action has shown users that their voice matters– something that’s of massive importance to Gen Z.

Though Gen Z is highly critical of corporations, they understand they must engage with them. The trade-off? They want to feel like the brands they support are listening to them.

The online landscape is too fast-paced for brands to attempt to dictate narrative– something that worked well on millennials (hello, magazine culture!) but doesn’t work on Gen Z. Rather, brands must make a concerted effort to understand Gen Z behaviours, habits, and choices.

Considering this, Bumble’s anti-celibacy campaign felt like a clear misunderstanding of the Gen Z experience. In making light of their sexual choices, the brand alienated the one generation it appeared to be targeting.

But a couple of weeks on, Bumble has largely been forgiven. The think pieces have stopped and the TikTok algorithm has moved on. In copping its mistake, Bumble was able to bounce back quickly– proving that ultimately, Gen Z doesn’t expect perfection from brands. They expect respect.

–

Top image: Lauren Meisner