In today’s hyper-connected digital world, the line between public and private life has become increasingly blurred. Social media platforms have created an environment where celebrities and public figures are more inclined to share raw, unfiltered moments from their personal lives.

Recently, radio host Carrie Bickmore shared a raw, tearful selfie where she openly discussed her mental health struggles and garnered widespread praise and support.

However, in the fickle world of social media, Bickmore’s post could very easily have had the opposite reaction.

Contrast Bickmore’s case with that of Hypersocial CEO Braden Wallace, who posted a crying selfie to LinkedIn back in 2022 after laying off a number of staff.

His intention was to show that “not every CEO out there is cold-hearted.” However, the attempt backfired. Instead of garnering sympathy, Wallace found himself at the centre of a global news story, widely criticised online for being out of touch.

Hypersocial CEO Braden Wallake

The power of ‘parasocial relationships’

Psychologist Sandy Rea explains that the difference lies in celebrities, like Bickmore’s, positive ‘parasocial relationships’ – a one-sided connection where fans feel they know and understand a public figure.

“Carrie is held in goodwill and high esteem,” Rea told Mediaweek. “Naturally, whatever happens to her is going to evoke sympathy, empathy, care, and compassion.”

Rea said the phenomenon makes the public feel like they know Carrie on an intimate level so “they understand her pain, and they understand her grief.”

This pre-existing connection, Rea suggests, likely provided Bickmore with a “safe space” to share her vulnerable moment. “I think that intuitively, she would be aware of that support and so this would be a safe space for her.”

Rea also emphasises the importance of context. “I think that’s another critical point to make: There’s a difference between revealing your mental health struggles and revealing your mental health struggles after you’ve done something egregious.”

This distinction is vital in understanding the differing reactions to Bickmore and Wallake’s posts.

“Bravo that she feels she can be authentic and has that kind of support from her relationships with people. That’s probably why she knew she was speaking to an audience that would accept what she said.”

However, Rea cautions, “Still, I think it’s also important to remember – celebrities and figureheads don’t owe us an explanation.”

“They also are humans who are very vulnerable and at risk, and that’s the same for Carrie. I’m ambivalent about people needing to explain their mental health struggles. I don’t believe people have an obligation to the public,” she said.

The perils of performative vulnerability

However, former advertising writer and social commentator Jane Caro raises concerns about the potential for vulnerability to be exploited.

“You have to be careful, and it has to be genuine,” Caro told Mediaweek.

“If it’s exploitative in any way, if you’re parading your emotions in any way – and I am absolutely not saying or think Carrie has done this – you have to be careful.”

Caro says that such displays can run the risk of becoming “performative” leading many to feel as though their empathy has been exploited.

“I worry that it can become performative in the same way that parading your awesome-looking life can become performative. Parading your misery can also become performative and start to look like you’re kind of begging for sympathy, so it must be handled with extreme caution.”

Caro also highlights the potential for negative backlash, particularly from those who may perceive a celebrity’s struggles as trivial compared to their own. “They think here is this well-off, healthy, famous, beautiful, accomplished, popular person; what has she got to be sad about?”

She acknowledges the inherent unfairness of this perspective, stating, “Now, that’s not fair. All sorts of people have all kinds of things to be sad about, and often, if you’re dealing with mental illness, it’s got nothing to do with whether you have a reason. You know that’s the problem with mental illness. It’s not reasonable, but that’s another reason. If you are dealing with mental illness, you need to be very careful with exposing yourself to the very things that are going to cause you more mental anguish.”

Caro also rejected Rea’s claim of Bickmore finding a ‘safe space’ to share her vulnerability: “I don’t care what kind of fan base you have; the media is not a safe space. They’re not the only people who will look and look. It’s all over the news now – nothing in the media is a safe space.”

Navigating the minefield

Ultimately, the success of a vulnerable selfie hinges on intention and authenticity.

As Caro suggests, “Always look at the intent. What’s your intent here? If you intend to get people’s sympathy, it won’t work. But if your intent genuinely is, ‘I want to show people that I’m not a superwoman, I am vulnerable, and that mental health is real, and lots of people who look like they’ve got bright, shiny lines in their lives actually struggle, too,’ then you know that’s a noble intent and good for you.”

Caro also warns that the public can be fickle and turn on a dime without any warning: “They can love your vulnerability one minute and think you’re a great, big crybaby the next”.

For Caro, the message of intent also applies to brands and businesses who are hoping to utilise vulnerability in their campaigns.

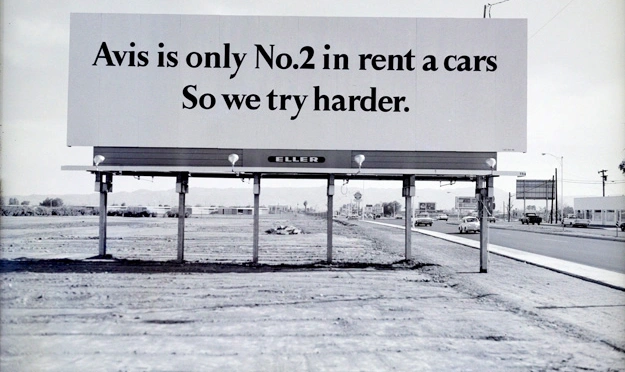

“If brands are going to show vulnerability, great, but do it like Avis,” she said.

Caro is of course referring to the car rental company’s ads back in the ’60s in which they acknowledged they were not number one in the market, but did so, as Caro describes in a “self-deprecating way”

“The ad worked because it was honest,” she explained.

“We’re acknowledging that we’re number two, but we’re also trying to get your business.There’s nothing wrong with vulnerability.”

Mediaweek has reached out to SCA for further comment.

If you or someone you know is struggling and needs help you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.