Deakin University graduate Luke Hunt is one of those rare critters – a busy and successful award-winning Asian-based freelancer who is not between full-time jobs.

He signs off his emails as “Opinion Editor: UCAN (Union of Catholic Asian News), East Asia Correspondent; Academic Program Professor, War, Media & International Relations, Pannasastra University of Cambodia”.

The introduction to his complex resume adds that he is also a regional correspondent for The Economist, The Diplomat, The Washington Times and the South China Morning Post.

Luke Hunt in Melbourne (c Morgan Reinwald)

This while also undertaking regular work for international radio networks like Voice of American and Radio Television Hong Kong, with occasional work for The New York Times, The Age and The Mekong Review.

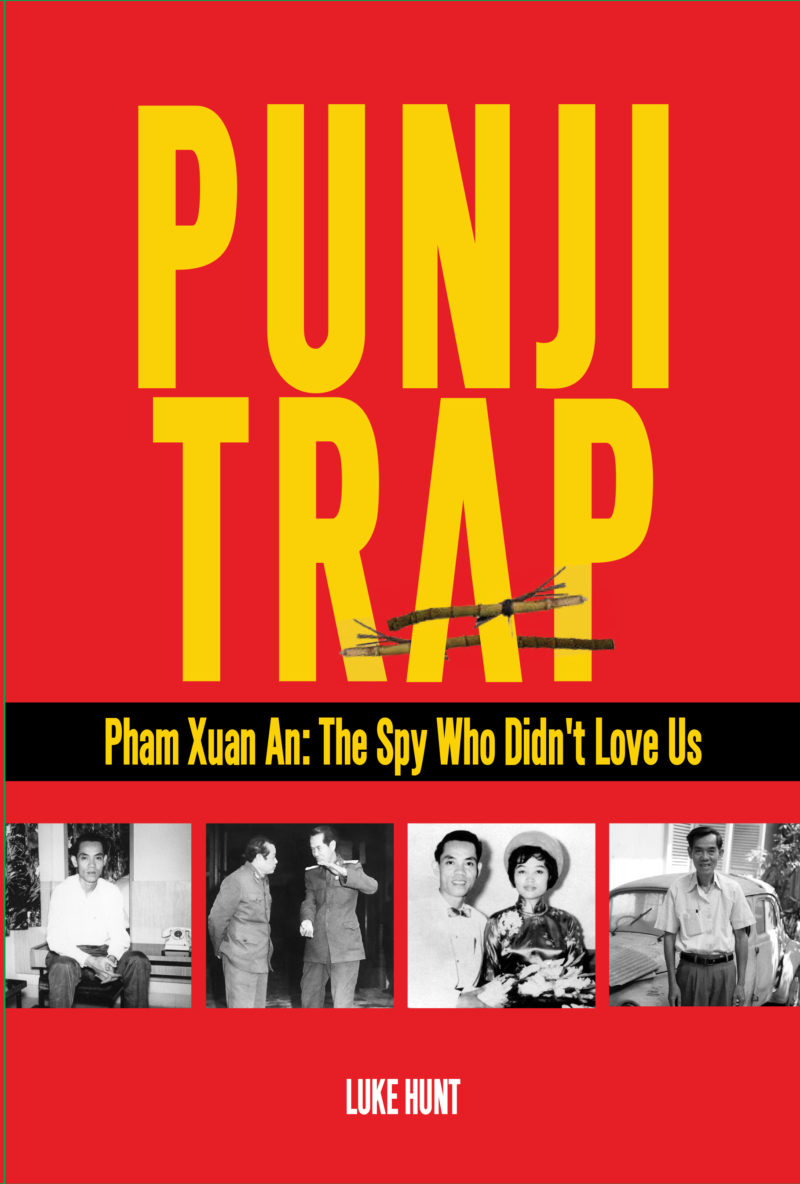

Plus he’s an author with a new book, “Punji Trap”, hot off the press this month, and in 1996, together with Karen Heinrich, he co-authored, “Barings Lost: Nick Leeson and the Collapse of Barings Plc”.

He’s adept at covering a wide range of issues, but his passion has been war zones.

“For any journalist there can be no greater story than the organised slaughter of humans by humans. It’s compelling,” he says.

Hunt, mostly based in Phnom Penh, is a seasoned Asian hand. “As a story, I find life in Asia is spell-binding,” he notes.

He first started working the region with AFX-Asia in 1995-98 and says, “AFX-Asia was a joint venture wire service set up by Agence-France Press and my previous employer Australian Associated Press, among others.

“I wanted to be in Hong Kong before the handover in 1997 and that was my ticket, and I covered the end of the British Empire for Australian newspapers and radio too.

“But the attraction goes much further back. Like the rest of my generation, I grew up on the Vietnam War that was playing out on the television. A family friend died there and that left its mark and helped spark a crazy fascination with the place.”

This month, Hunt has been hunkered down at a print shop in Phnom Penh, supervising the birth of his new book “Punji Trap – Pham Xuan An: The Spy Who Didn’t Love Us”.

The book’s blurb says, “Pham Xuan An was a Communist agent whose espionage adventures – under the cover story of a celebrated war correspondent in the Western media — were as brilliant for Hanoi as they were shattering for Washington during the tumultuous days of the Vietnam War.”

Hunt began working the story about 28 years ago. “I wrote an undergrad thesis on An way back when his role in the Vietnam War was still a secret,” he says.

“Then I managed to get into Vietnam as the Cold War was ending with introductions which An could not refuse, and I realised then that there was certainly a book in him and the people that helped me get there.”

He’d put writing the book on hold for many years because, “Much of the information was deep background and to remain so until my sources were dead. Hence the long wait.”

Initially, An was also hesitant about the book. “At first he was understandably gun shy because he was always in trouble with the authorities. Life under Communism did not always suit him,” Hunt says.

“But he wanted his story told and was generous and friendly. I earned his trust over the years and what he told me was off the record until after his death, which was in 2006.”

The book also looks at the role of foreign correspondents covering the Vietnam War, and generational differences in war reportage.

“The big differences between WW2, Vietnam and wars now are that back in the day people from all sides – military, press, politicians and the like – respected D-notices and journalists were on the same side of the militaries they were covering,” Hunt says, adding that technology has also had an enormous impact on conflict coverage.

“Now there are too many armchair war correspondents tweeting opinions,” he says, “which to a point is understandable given groups like ISIS have made frontline coverage by independent journalists almost impossible. Their predilection for hacking the heads off the messenger was as chilling as it was almost without precedent.

“The advent of smartphones and the digital age also means the demand to send Western-trained journalists into battle is not as great as it once was.

But he adds that the need for solid objective reporting is still there.

Hunt sums up his war coverage as, “My proudest boast is that no one who worked with me got hurt on any of my jobs. I wish I could say that about my friends and colleagues who got hurt or killed.”

Top photo: Hunt with Taliban soldiers in Afghanistan, 1998 (c Mohammad Bashir)

Punji Trap: published by Pannasastra University of Cambodia Press. International distributor: Talisman, Singapore. Will be available on Amazon, print on demand and Kindle. International retail price: US$18